If you’ve talked to your pediatrician or registered dietitian about feeding strategies, then you are probably familiar with Division of Responsibility. The Division of Responsibility can help set appropriate boundaries around food, while giving the child opportunities to have some control. This can be helpful for parents with children who struggle with eating- whether they are “picky eaters” or preoccupied with food and always wanting to eat

What is the Division of Responsibility?

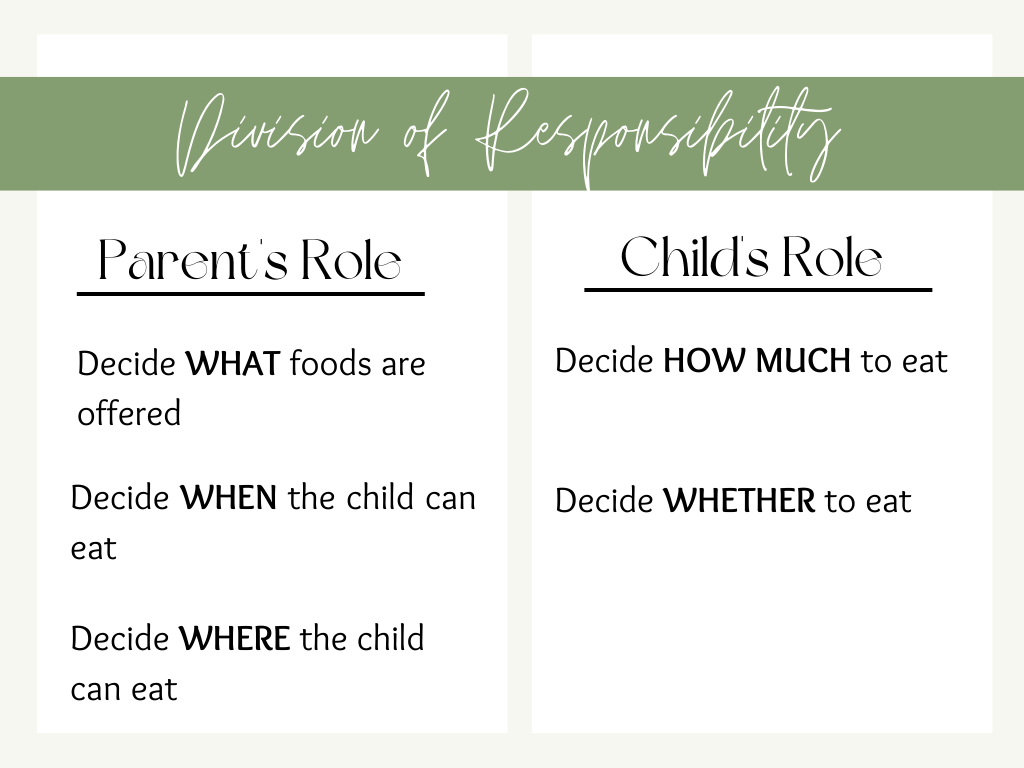

Ellyn Satter developed the feeding method known as The Division of Responsibility (DOR), which suggest that parents should be responsible for what, when, and where the child eats. While the child, should be responsible for deciding whether they eat, and how much they eat. Giving children the ability to make choices at mealtime helps decrease their need to fight for control, empowers them to listen to their hunger and fullness cues, and helps build healthy eating habits through positive and safe experiences around eating.

Define your Role: Deciding What, When, and Where Your Child Eats

What your Child Eats

Parents are responsible for deciding what to feed their child. Offering food that provides nourishment and food that they can enjoy are equally important. As young children start eating solid foods, parents need to make sure they provide opportunities to meet their nutritional needs for calories, protein, and essential nutrients such as iron, vitamin D, and Calcium. This can come from food, or from supplements if they are more selective eaters. Parents can offer new foods along with foods that the child is comfortable with. For adopted children, this might mean providing culturally familiar options that they enjoy. Understanding each child’s needs- whether there are sensory issues, oral motor delays, or cultural preferences, is important in helping children develop into competent eaters. When food feels safe, kids can eat better.

When Your Child Eats

Scheduling meals and snacks throughout the day (generally about 2-3 hours apart) helps decrease anxiety around eating and helps avoid grazing throughout the day. Knowing that an opportunity to eat will come can help children feel reassured as they learn to trust their parents as reliable providers who meet their physical needs. This is particularly important for children who have had a difficult start.

Routine family meals and snack times can foster a sense of felt safety particularly for kids with complicated histories. Children with a history involving institutional care, food insecurity, medical conditions or trauma will need extra support with feeding. Sometimes the fear of not having enough food can be hard to overcome even when food is abundant. Some children will feel reassured knowing that there is food available to them at all times. Parents can still follow the DOR, adjust the feeding schedule when necessary, or choose to make some food available all throughout the day. The key is to be in tune with your child’s unique needs, and help them to feel safe.

Where Your Child Eats

When we think about where meals and snacks are eaten, we usually picture kids sitting with their family at the dinner table. Family meals can be great opportunities for connection and learning. But the idealized meal environment can be impractical for many families these days. Parents need to consider the needs of the each individual when deciding where meals and snacks are eaten. Is there enough space for everyone to have a seat at the table? Will the child be able to tolerate the noise, lights, and smells? Families may need to eat their dinner while sitting in traffic on some days. Eating in the car can be enjoyable too!

Define Your Child’s Role: Deciding Whether and How Much to Eat

When children are able to decide how much they eat, or whether they eat at all, they can learn to listen to their internal cues. Giving your child the opportunity to make choices is empowering. Often, our mealtime battles have to do with so much more than just food. Allowing your child to be in control of how much they eat, or whether they eat at all decreases the need to fight for control. This means parents aren’t forcing them to clean their plate, pressuring them to take one bite, or shaming them for eating too much or too little.

Giving children control over how much they eat can take a lot of practice for parents. Adults who have grown up in cultures where there was pressure to eat a certain way can have a really hard time staying neutral to their child’s decisions and trusting their child’s instincts. Parents often have an opinion about how much children should eat. Letting go of the fear that they will be hungry, or that they will overeat, gives children the opportunity to listen to their internal hunger gauge.

How Does the division of Responsibility Work For Kids with extreme picky eating or a feeding disorder?

Kids with feeding disorders, such as Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder (ARFID) can have a very limited number of foods that they are willing to eat. This is different from normal picky eating because these kids can have extreme reactions and sensitivities to certain foods, textures, or smells. Decreased interest in food and eating can be related to sensory processing differences or past trauma experiences and oral aversions. Their limited intake is concerning because it affects their growth and nutrition. Parents can still follow the DOR, but must be considerate when choosing what to feed the child. When foods that are normally considered “healthy” are foods that the child has a hard time eating, parents can explore other options to accommodate for their child’s differences. Finding different ways to meet their nutritional requirements is important as the child learns to accept new foods.

How does the division of Responsibility work for kids who are “overweight”?

Labeling children as “overweight” or “obese” leads to the common misconception that some kids need more restrictions around food. These labels, often based off a BMI calculation, don’t account for different body types. Restriction around how much a child eats can create even more anxiety around food and increase mental preoccupation with eating. Parents often feel pressure to restrict their child’s intake, but this can cause an opposite effect. Regulating food intake and tuning into their natural hunger and fullness cues is harder when food feels limited. By following the DOR, parents give children permission to eat as much as they want. They may eat way more than parents are comfortable with. But over time, the child will learn to regulate and develop a more healthy relationship with food.

Can you implement the division of Responsibility with neurodivergent kids or kids with past trauma experiences?

Children with Autism, ADHD, FASD, sensory processing differences, or past trauma experiences can have different challenges around mealtime. A history of food insecurity, neglect, or simply moving from one culture to another contributes to complicated feeding challenges for some foster and adopted children. Additionally, different medications can affect their natural ability to regulate intake.

Sometimes, what’s considered “best practice” isn’t necessarily what’s best for every family.

While using DOR for these children is certainly possible, each case should be considered individually. Parents must learn to accommodate for their child’s needs when deciding what, when, and where to feed. Prioritizing felt safety is more important than sticking to structure and following guidelines. Each family’s experience and situation is unique. Sometimes, what’s considered “best practice” isn’t necessarily what’s best for every family. Creating space for connection may require a compromise in some areas, or a new definition of what “healthy eating” means. Talking to a registered dietitian who is trauma informed, can be helpful, as you figure out what works for your specific situation.

Things to consider before implementing the division of Responsibility in your family

Before implementing DOR in your home, it’s important to do some self reflection about your own beliefs about food and childhood experiences around eating. Next, make sure that the adults involved in feeding are all on the same page. This may require discussions with a spouse, grandparent or caretaker. When the adults who are feeding the child provide an environment with consistent boundaries, the child will learn better. Keep in mind that the goal is to create a safe space for kids to eat well. Not everyone will do things perfectly, and learning to follow the DOR will take time and practice. Be mindful that implementing these new feeding guidelines in your home doesn’t create a more stressful environment for the family. Extend grace to yourself, and to each other.

What to expect when you start implementing the division of Responsibility in your family

As with many parenting styles, the learning curve can be steep, and behaviors can escalate before they get better. Feeding will likely feel more challenging in the beginning before there are signs of improvement. When kids notice that rules have changed, they will test their boundaries. They might eat way more than you’re comfortable with, or they may refuse meals all together. It takes time, but with persistence, consistency, and a lot of patience, children can learn to be competent eaters. Contact us to see if working with a Registered Dietitian would be helpful for you.